In the morning when he awoke, Elie immediately remember his father and jumped out of his bunk, running off to search for him. His search lasted for hours, ending when he found his father near a block where they were distributing black "coffee." Elie did not spot his father, but his father's cry to his son for a drink of coffee brought Elie to him. Elie fought his way through the crowd, successfully bringing his father back a small cup of coffee. Elie saw in his father's eyes the gratitude like no other, saying "With these few mouthfuls of hot water, I had probably given him more satisfaction that during my entire childhood..."

Every day, Elie's father grew weaker and weaker, his face becoming "the color of dead leaves." Elie tried his best to care for him as best he could, but someone suffering from dysentery in those conditions, there was nothing that Elie could do to help him. In his father's dying hours, he desperately tried to tell Elie all his life secrets and words of advice. He even told Elie of the families buried gold and silver, buried in the cellar of their home. A week went by with Elie trying desperately to meets his father's desires and avoid the ridicule of the other inmates for taking care of a hopeless cause like his father. One of the doctors even told Elie that he must stop giving his bread and soup to his father. Such a thing in a concentration camp would surely bring about his death.

When roll call came, Eliezer decided that he would remain with the sick and he stayed in his bunk to be with his father. As he lay there, he father began to cry out for water, calling his name, "Eliezer... Eliezer!" One of the guards shouted for silence across the barrack, but his father payed not attention. He only continued crying out, "Eliezer... water my son. Water! Eliezer." The officer then came over and struck him brutally on the head. Elie couldn't move, he was too afraid. Afraid that the next blow would be to his head. He climbed down after roll call, finding his father mumbling and shaking. Finally, after staring endlessly at him father's crumbled and broken body, Elie crawled into his bunk to sleep. The date was January 28, 1945.

The next morning, Elie woke upon at dawn. January 29. In his father's place lay a new sick person. His father had been taken from him. But much to his confusion and pain, Elie had no tears. He did not weep. He could not bring himself to cry when there were no tears left.

Three months later, Elie Wiesel's story comes to an end. He does not describe the remain months that he spends in Buchenwald. With the death of his father, nothing more could have mattered to him. He sat in idleness for three months, only thinking of food, the next bread and soup that he would receive.

On April 5, all things changed. They were waiting in the afternoon for a Germany officer to come and count them. But he was late. Late! This did not happen ever, not once in the history of Buchenwald's operation. After two hours of unknowning, the loudspeakers announced that all Jews were to report to the Appelplatz. In the confusion, of the masses heading towards the Appelplatz, many Jews had passed as non-Jews. This could not be tolerated by the camp's command, so they decided that a general roll call would be held the next day with everyone present. After the following day's roll call, thousands upon thousands were marched out of the camp's gates each day. On April 11, with twenty thousand prisoners still remaining, the resistance decided to act. They appeared everywhere, armed men with rifles, machine guns, and grenades. The battle was short and the SS fled the compound, leaving the resistance victorious.

The first action that all the prisoners took after their liberation was to gouge themselves on the provisions. Elie describes their thought process. "[P]rovitions. No thought of revenge, or of parents. Only of bread." Instinct had taken over emotion and ending their hunger was all that mattered.

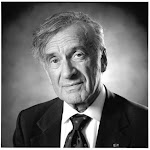

Elie became sick three days after the liberation. Food poisoning. He clung to life, swing back and forth towards death for weeks in the hospital. As he stayed in the hospital, he decided to find a mirror and look at himself. He had not seen himself in years. Since he was back in the ghetto of Hungary. Staring back at him was "a corpses... contemplating me."

.jpg)